C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

It is only too evident that the Modi government is a strongly centralising one in many ways – and this is also clear from various fiscal moves. In 2015, it accepted the recommendation of the 14th Finance Commission to increase states’ share in total tax revenues, from 32 to 42 per cent. But it simultaneously cut plan grants and sharply reduced the Centre’s share of spending on Centrally Sponsored Schemes, almost neutralising any benefit to states. The imposition of the Goods and Services Tax in 2017 denied revenue-raising powers to states, creating further fiscal centralisation.

But since then the government has turned even more aggressive. It increasingly relies on cesses and surcharges that do not have to be shared, and when it offers tax cuts, it makes them on the shareable pool of taxes rather than the cesses. It has asked the Finance Commission to reconsider the increase in offer to states – an unprecedented move – and even wants to disallow any revenue deficits of states.

What explains this niggardly approach to state governments? It cannot be politics alone: most states now also have BJP-run governments. The answer might lie in the contrary movement of central and state spending in recent years, which points to the mess the Centre has made of its own finances.

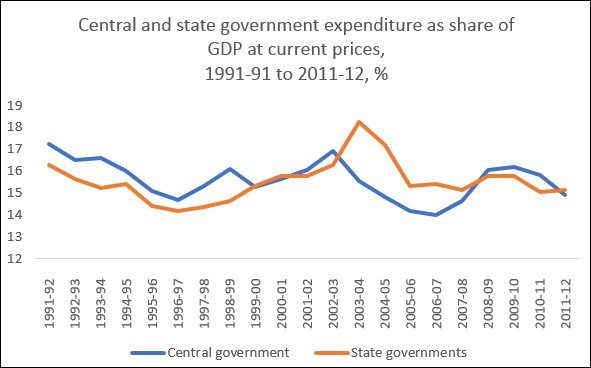

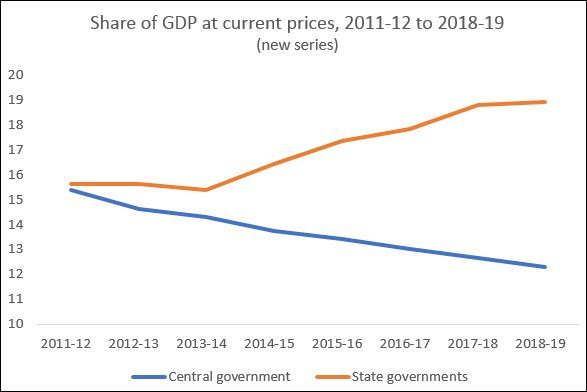

Figures 1 and 2 point to an interesting break in trend. Until 2011-12, the Centre and all the States together spent roughly similar shares of GDP on all forms of expenditure, and even showed similar cyclical patterns. However, after 2013-14 there has been quite a sharp divergence, with state governments spending significantly more in terms of proportion of GDP. The difference in the latest year was as large as 6.6 percentage points of GDP.

To some extent the increasing expenditure of the state should definitely be welcomed, as they are together responsible for the bulk of goods and public services that affect citizens’ lives, ranging from economic services like those for agriculture and infrastructure to social services like health, education, sanitation and essential services like security. Since these are currently underprovided in India (keeping in mind the very large state-wise variations) all spending that increases these services in both quantity and quality must be good for people. Also, since public spending is an important element of ensuring aggregate demand and can play a crucial countercyclical role, this is also important for macroeconomic reasons.

Figure 1: Until 2011-12, the centre and all state governments

together spent roughly similar shares of GDP

Figure 2: But in recent years, state governments together have spent much more

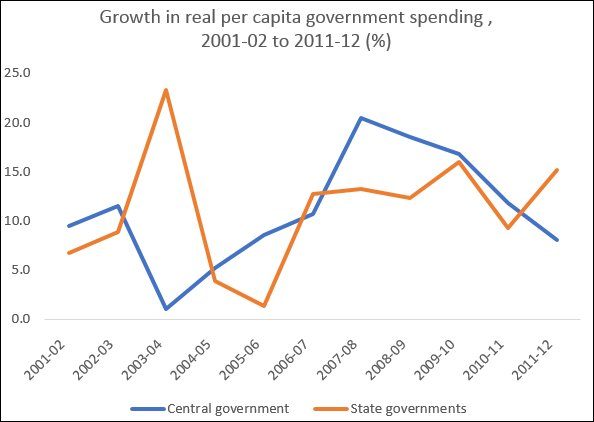

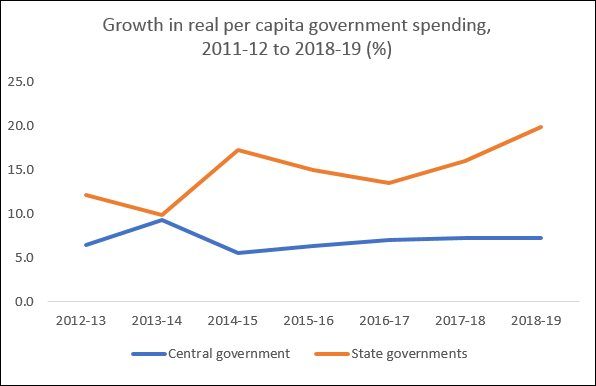

Figures 3 and 4 indicate a similar pattern when it comes to per capita real spending of the Centre and States. (These show total spending deflated by the GDP price deflator and divided by population projections from the Registrar General of India.) The rapid increase in state governments’ spending in the past few years is indeed remarkable.

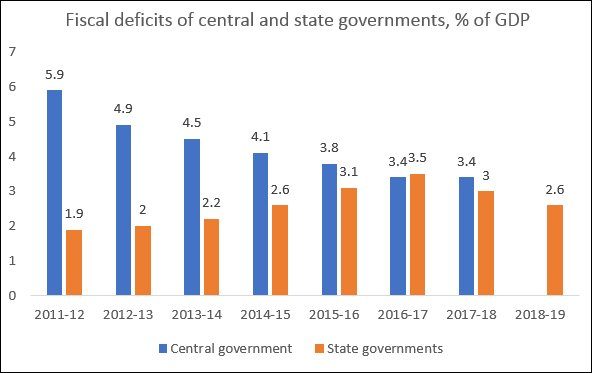

Lest it be argued that this has come about because of greater fiscal profligacy of state governments, Figure 5 puts such doubts at rest. In fact, state governments have been on a very tight fiscal leash with fiscal responsibility legislation tying their hands and preventing them from running capital account deficits at all, while putting strict limits of 3 per cent on revenue deficits. It is clear that throughout this decade, the Centre has generally run larger deficits than all state governments put together, despite the fact it has had much greater revenue raising powers and greater fiscal flexibility in general.

Figure 3: Even in real per capita terms, Centre and States

spending moved mostly together until 2011-12

Figure 4: Since 2013-14, state governments’ per capita real

spending has increased much faster

Figure 5: State governments have generally been more

fiscally responsible than the Centre

However, this pattern may be set to change now, with the intensification of the Centre’s attempts to concentrate fiscal resources in its own hands. The implications are of great concern not only to fiscal federalism and the federal structure of our democracy in general, but also for dealing with the current slowdown. Two features of the Centre’s recent behaviour are relevant here. First, the Modi government’s obsession with keeping tight control of its ‘on-budget’ fiscal deficit, make expenditure increases dependent on special resources such as privatisation receipts and transfer of RBI surpluses to the government. That limits the level of spending. Second, when the government does use the fiscal lever to provide a stimulus to a slowing economy, it relies on tax concessions to corporates and upper income groups, rather than on increased spending. This is counterproductive, not only because it involves a transfer of incomes away from those with a greater propensity to spend to those who would devote a lower share of increased incomes to expenditures of different kinds, but also because it worsens the resource crunch faced by the government and results in lower government spending.

Given these features, it is likely that it has been state government spending that kept some economic activity going in recent years despite various blunders like demonetisation and the terrible implementation of the ill-conceived GST. But now state governments are also being prevented from spending more, precisely when more public spending – especially in employment-intensive activities – is the need of the hour.

The Modi government has already shown that it is quite clueless in dealing with the ongoing economic slowdown, and is persisting with supply-side measures that are unlikely to have much positive effect in a situation of inadequate aggregate demand. Worse still, it is preventing the state governments from rising to this economic challenge.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on October 8, 2019)