C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

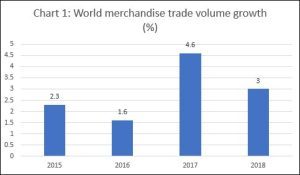

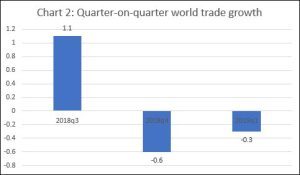

World trade is in deceleration mode. After having recovered smartly from 2.3 and 1.6 per cent in 2015 and 2016 to 4.6 per cent in 2017, the growth in the volume of world merchandise trade slowed to 3.0 per cent in 2018, WTO estimates show (Chart 1). The deceleration has been greater in recent quarters. Quarter-on-quarter growth rates, as estimated by the Netherlands Centraal Planbureau (CPB) indicate that trade growth fell from 1.1 per cent in the third quarter of 2018 to -0.6 per cent in the fourth quarter and -0.3 per cent in the first quarter of 2019 (Chart 2).

The prognosis is not positive either. The WTO’s World Trade Outlook Indicator (WTOI) released in May 2019, for example, stood well below its baseline value of 100 at 96.3, which is its weakest level since 2010. That signals that world trade growth has fallen in the first half of 2019. Moreover, according to the WTO: “The outlook for trade can worsen further if heightened trade tensions are not resolved or if macroeconomic policy fails to adjust to changing circumstances.”

Given the intensification of the trade and tech war against China unleashed by the US, with several rounds of tit-for-tat imposition or escalation of tariffs and leading into a US effort to paralyse the Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei, this trade slowdown is often attributed to the disruption caused by this stand-off. While the role of US economic aggression cannot be denied, there is reason to believe that that cannot be the whole story. The effects of the trade war work in multiple ways, making the magnitude of the net negative effect on the volume of world trade uncertain. The signs of a medium term loss in the momentum of trade growth perhaps signal one more step down the path to a global recession.

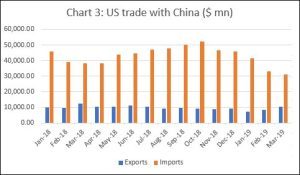

China has been the main loser in the trade war. US imports of Chinese goods have fallen from $52.2 billion in October 2018 to $31.2 billion in March 2019, compared to $38.3 billion a year earlier. The effect on the US has been smaller in absolute terms, with US exports to China having fallen from a lower $12.4 billion in March 2018 to $10.4 billion in March 2019 (Chart 3). This is partly because China has been circumspect in responding to the provocative measures adopted by the Trump administration, given its own persisting dependence on exports, even as it seeks to rebalance growth away from exports and in favour of the domestic market.

This is, of course, the direct effect of the US attempt to browbeat China on grounds varying from unfair trade policies and practices and coercive appropriation of intellectual property from US firms to adoption of measures that threaten US national security. That triggers in turn second-order effects, which result partly from adoption of similar measures relative to other countries (true especially of the US with respect to Europe for example), and partly from the fall-out of the growth deceleration and consequent fall in imports resulting from the US-China showdown, which would be more significant in China. China, because of its rapid growth and growing demand for raw material and intermediates, and because it has served as a final-stage export platform for global production chains, has been a major source of import demand in the world economy. So any slowdown in China resulting from the US actions is bound to affect world trade adversely.

However, the trade war triggered by US actions also has positive effects on growth both within and outside China. To start with, it would result in a diversion of the export trade to the US and China, away from Chinese and American exporters to suppliers from third countries. To the extent that there is such trade diversion, the total volume of world trade is unaffected. Further, to the extent that Chinese and US producers, restrained by import competition in the past, benefit from the new protectionism, the growth-reducing effects of the protectionist actions would be neutralised. Taking these factors into consideration, and noting that the effects of the trade war are still working themselves through, the recent slowdown in world trade must be explained by a more generalised slowdown in world demand. The slowdown in import growth is visible in all locations except the US and Japan, with the deceleration being significant in the Euro area, Other advanced economies, Eastern Europe/CIS and Latin America, and import volumes stagnating in Africa and the Middle East. Growth of imports in value terms showed up a better picture, largely because the prices of fuels which had fallen by 14.6 per cent in 2016, registered positive increases of 22.2 per cent in 2017 and 27.2 per cent in 2018.

What is noteworthy is that the deceleration in import volume growth has been particularly marked in the emerging economies of Asia and Latin America, pointing to a loss of momentum in the countries that were expected to be new growth poles in the immediate aftermath of the 2007 crisis. Leading the decelerating trend was China, with imports into China falling 4.8 per cent in the first quarter of 2019, when compared with a year earlier.

What this points to is a more generalised depression of global demand, resulting in a loss of growth momentum. This is not captured adequately in the first quarter GDP numbers that have transformed the pessimism reflected in the April 2019 edition of the IMF’s World Economic Outlook into the optimism seen in some of the subsequent assessments of global growth prospects. The fundamental failure is of the policy adopted by leading OECD countries of reliance on monetary measures to pull the economy out of the recession that set in a decade ago. That failure has led to the backlash against corporate-led globalisation that has taken a peculiar turn in the form of the rise of Trump, the Brexit mess, and the ascent of the far right in Europe and elsewhere. A real global recovery requires different strategies.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on June 3, 2019)