Question: How will Brexit affect the UK budget deficit / national debt / public finances?

One of the low points of the Brexit campaign was when the chancellor of the exchequer George Osborne announced a vote for Brexit would lead to higher taxes and lower spending straightaway. Dubbed the ‘punishment budget’ it probably had the opposite effect and encouraged people to vote – against Osborne / for Brexit. Voters quite rightly disliked the explicit threat that if you vote against me, immediately taxes will go up. Also, fundamentally Osborne was wrong to say, in the short term taxes would rise.

- If there is an economic downturn, it is better to relax fiscal rules than compound the economic downturn with deflationary fiscal policy.

- If Osborne lost the EU vote, he would be out of a job anyway. Ironically, one of his last acts as chancellor was to suggest cutting corporation tax.

- There will be no tax rises in the next budget, despite a Conservative manifesto pledge to balance the budget by the end of the parliament.

Fiscal costs during exit period 2017-20

But, what about the next few years? How will Brexit negotiations and preparations to leave the EU affect the public finances?

- Lower economic growth rate in 2017 will lead to lower tax revenues.

In 2017, many forecasters have stated the UK is likely to experience lower growth of 1% (as opposed to 2.2%) This lower growth will be caused by:

- Uncertainty over direction of UK, leading to lower investment.

- Falling Pound reducing disposable income and leading to lower spending.

- Decline in FDI as firms wait to see outcome of UK / EU negotiations.

- Fall in net migration (due to foreigners feeling unwelcome in Britain) will adversely affect GDP and tax revenues.

On the positive side to growth, the devaluation of Pound will provide a boost to exporters, and the loosening of monetary policy will provide some stimulus. It is possible the government may pursue expansionary fiscal policy (borrowing more to finance public sector investment)

However, so far, average forecasts expect lower growth through 2017 and 2018. This will lead to lower tax revenues (or more accurately slower growth in tax revenues than expected.) Government spending will increase at a faster rate.

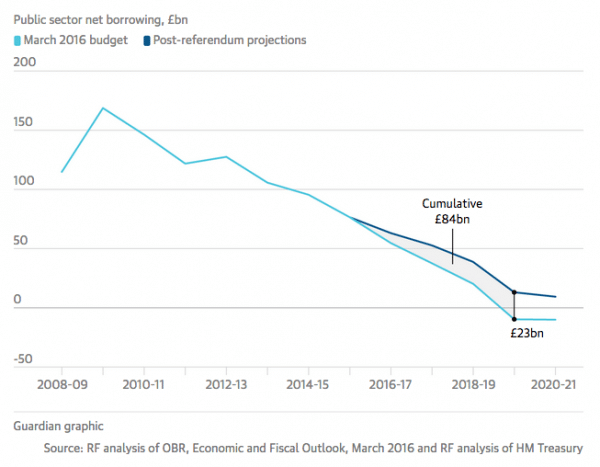

The Resolution Foundation predict, Brexit could lead to a deterioration in public finances of £80bn by the end of the parliament. This is a figure that will either lead to higher borrowing or lower spending.

The Resolution Foundation predict, Brexit could lead to a deterioration in public finances of £80bn by the end of the parliament. This is a figure that will either lead to higher borrowing or lower spending.

Unfortunately, recent borrowing figures have not been good, with unexpectedly low corporation tax receipts last month.

Fiscal Costs of leaving EU

When the UK finally leaves, how will that affect public finances?

On the positive side, the UK will no longer make the net payment to the EU of £7.1bn (see: cost of EU – which also has other figures) The UK could save more, if for instance it didn’t compensate farmers, universities and other recipients of EU aid. (like Cornwall and Wales)

However, there is a precedent for countries outside the EU paying into the EU budget anyway. Norway’s per capita spending on the EU isn’t much different to the UK’s net contribution. I would argue it is very likely the UK will end up paying a significant amount of money in return for a deal on restricting labour, but retaining some kind of access to single market. The EU need the money. The UK wants a deal to restrict labour but still retain privileges for bankers / access to single markets. The only way around this is to get the UK to pay a lot of money.

Other points to consider

Any decline in the financial sector will hit income tax revenues hard. A very large percentage of UK income tax receipts are paid by a very small section of the economy. Bankers in London may not be the most popular section of society, but they do pay a lot of income tax (because they get paid so much more than everyone else). If the EU exit does lead to an exodus of banks, this will be a very large hit to public finances, which will be difficult to make up from elsewhere in the economy.

Of course, some argue UK is suffering from a financial form of “Dutch disease” and rebalancing the economy away from banking to something else may have long-term benefits. This may well be possible, but at least in the transition period, the UK would suffer from a decline in tax revenues.

Net migration. Migrants provide a net gain to the public finances (migrants mostly of working age). If we cut migration levels, this will negatively affect public finances.

Outside the single market. The UK may well end up with diminished access to the Single Market. The EU will want to send a clear signal that if you leave the EU, you pay a penalty. There will be no magical deal where we get all benefits without free movement of labour. Higher tariffs (and importantly non-tariff barriers) could adversely affect trade, FDI and economic growth. Many economists modeled approximately a 2% fall in GDP (not a recession, but a slower growth rate leading to cumulative 2% decline in output.) This of course will adversely affect tax revenues and public finances.

Conclusion

Many voted to leave the EU – not because they don’t like foreigners or were philosophically opposed to EU – but because they want better public services – health care, housing and education, and they were led to believe leaving EU would improve living standards. However, it is hard to see how the UK finances can improve, given all the factors weighing down the UK economy post-Brexit vote. If anything, future chancellors are going to have a diminished choice, leaving less tax revenue available for public spending.