What does it mean to talk of labour market slack? And how is it measured?

Essentially labour market slack is the shortfall between the volume of work desired by workers and the actual volume of work available.

Labour market slack also determines the difficulty or ease of employing more workers. When there is labour market slackness, there will be many applications for available jobs and firms will have no difficulty filling labour market vacancies.

When labour market slack is reduced and the labour market ‘tightens’ – firms can face difficulties filling vacancies and the economy will be close to ‘full employment.’

A tight labour market

During a period of full employment, low unemployment and difficulty filling labour vacancies, there will be very little labour market ‘slack’. We can state that the labour market is ‘tight’. Firms have to compete for the limited number of available workers. When the labour market is tight (little slack) then it tends to cause:

- Upward pressure on wages. Firms struggle to fill vacancies so to attract skilled workers they offer increased wages.

- Low unemployment

- Rising employment and rising participation rates. (people active in the labour market)

- Average hours worked rising as firms deal with labour shortages by encouraging workers to do overtime.

- Firms are more willing to employ less skilled workers and undertake the training themselves.

A slack labour market

If a labour market has a considerable degree of slackness, then employers find it very easy to employ extra workers. A slack labour market will occur during a period of high unemployment. It will tend to cause

- Stagnant real wages as firms do not need to increase wages to attract workers

- High unemployment

- Low employment levels and falling participation rates.

- Fall in average hours worked as firms increase the use of zero hour contracts and employ workers for fewer hours. This causes a rise in underemployment

- Rise in part-time and temporary work.

- Workers are more likely to be over-qualified. With labour market slack workers more likely to accept low-skilled jobs that don’t match their qualifications.

Measuring slackness in the labour market

There are different ways that the degree of slackness in the labour market can be measured.

- Unemployment rates – The unemployment rate

- Unemployment rates compared to the natural rate of unemployment

- Employment rates

- Measuring the shortfall in hours labour workers compared to desired hours.

- The ratio of vacancies to unemployment rates

- Underemployment index which includes both jobs and hours worked

Unemployment

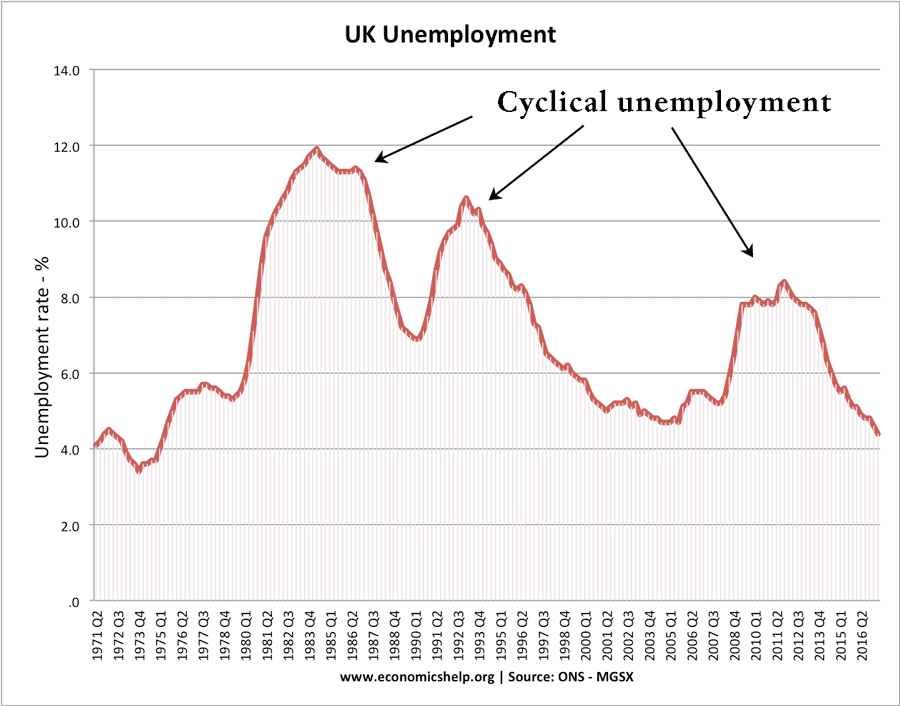

Periods of rising unemployment show rise in labour market slack. Falling unemployment indicates a ‘tightening of the labour market’

The unemployment rate is an easily available statistic. Falling unemployment indicates a decline in labour market slack. However, it can be a mistake to only focus on unemployment rates. Unemployment statistics ignore

- Fall in participation rates – people leaving the labour market, though might be willing to re-enter if better jobs are available.

- The number of hours worked. If you would like to work full-time, but only get part-time hours, you are not counted as unemployment

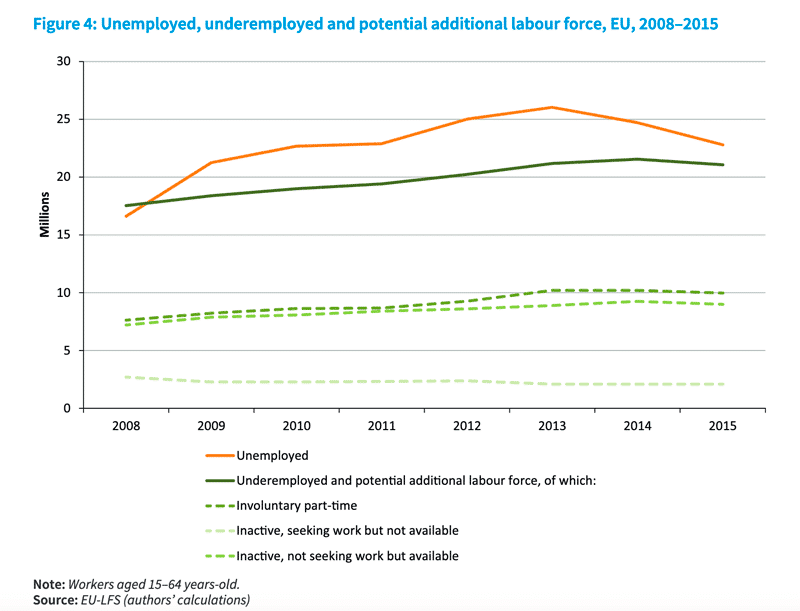

The EU estimated labour slack rate in the EU rose between 2008 and 2015 (from 11.8% to 14.9%) This was a bigger rise than the increase in the unemployment rate (from 7.1% to 9.5%). (EU)

One of the biggest reasons for the rise in labour market slack was a fall in participation rates -, especially amongst older men. The biggest reason given for leaving the labour market was ‘discouragement’ – the feeling good quality jobs were not available any more.

Factors behind the labour market slack in the EU

Another significant factor of labour market slack was ‘involuntary part-timers’ people who would like to work full-time, but only have part-time hours. There were 10 million involuntary part-timers in the EU survey.

Source: EU-LFS

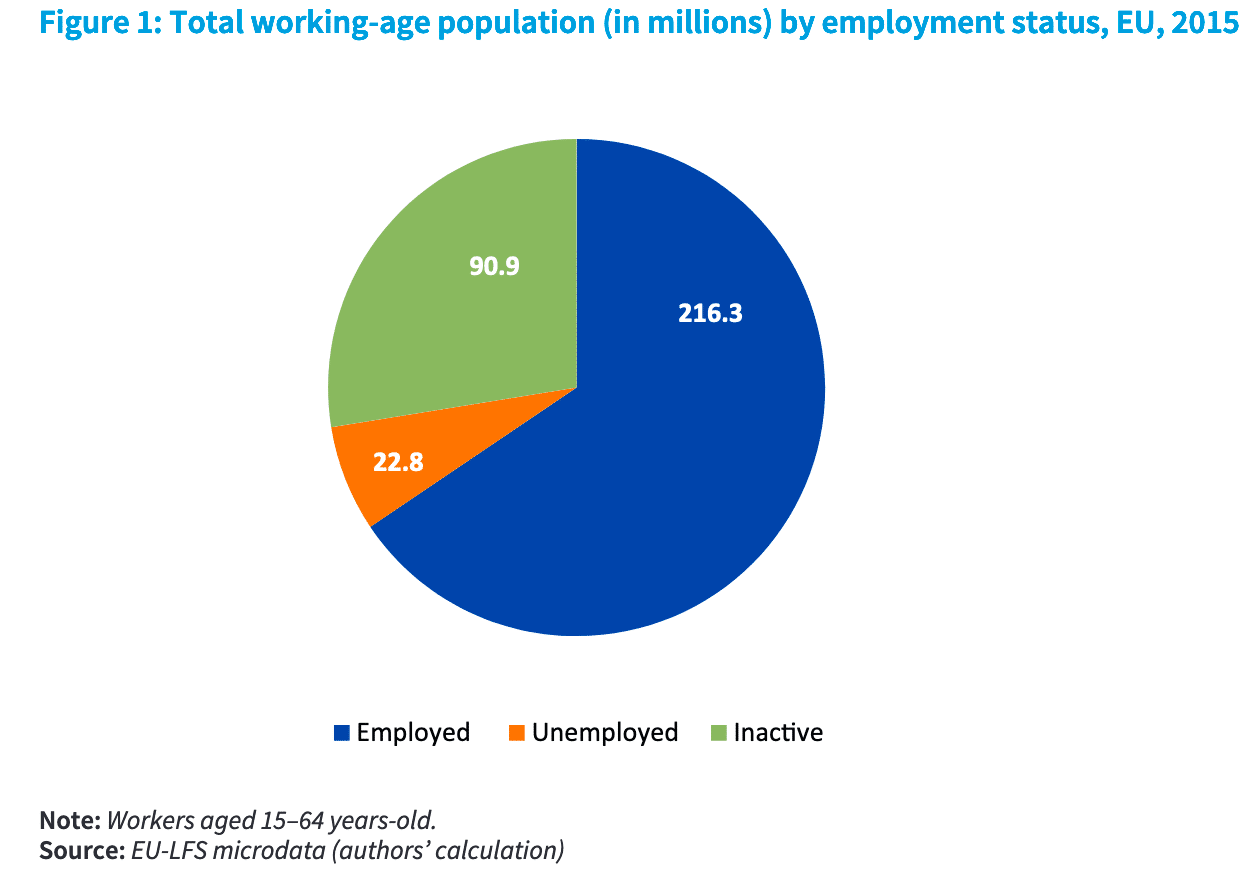

The ratio of EU labour force.

Importance of labour market slack

The degree of labour market slack is very important for monetary policy.

For example, the fall in unemployment in the UK and US close to 4% – would indicate that the labour market has little slack. Usually, this would be an indicator the economy is reaching full employment, and it would justify an increase in interest rates. However, in 2018/19, this fall in unemployment is an unreliable guide to labour market slack. (It ignores underemployment e.tc.) wages are not rising – indicating there is still slack – despite the fall in employment.

- Structural slack. Labour markets can have shortages in certain areas which require particular skills. e.g. it is hard to fill vacancies for builders or nurses; this may require training and education to deal with particular shortages

- Immigration policy. A labour market that exhibits little slack may benefit from allowing greater levels of net migration to prevent an overheating labour market and shortages of labour. Equally, large levels of slack may act as a discouragement to migration.

- Participation rates. Large degree of slack during a period of low unemployment suggests there is a problem with labour market participation. For example, recent reports suggest, western economies have an issue with a rise in self-reported disability, labour market discouragement and early retirement.