C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

With India’s development strategy relying increasingly on private investors across industrial and infrastructural categories, the question of how private investment would be financed has moved to centre stage. This question has gained in significance not merely because areas earlier reserved by the public sector are now expected to be led by the private sector, but because the development finance institutions that in the past had, with state support, financed a substantial chunk of private investment are no more in existence, having been converted into commercial banks. How then has private investment been financed in recent years?

Recently released flow-of-funds data for the period 2011-12 to 2017-18 (Reserve Bank of India Bulletin, July 2019), point to some changes in the pattern of financing of the activities of private non-financial corporations. On the supply side, households seem to be inclined to move away from bank deposits to other financial assets, providing an opportunity for the corporate sector to access direct finance through the issue of equity and debt securities. And, interestingly, on the demand side, private corporate investors seem to have relied more on internal resources and equity finance rather than on borrowing in the six years ending 2017-18.

The Reserve Bank of India,, given its concerns, has presented evidence on the net financing by source of the financial deficit of the private corporate sector. But, when considering the pattern of financing of corporate activities it is preferable to consider gross financial flows. Firms receiving financing are not the same as the ones returning capital borrowed in the past or acquiring financial assets with surplus cash. If the concern is the financing of ‘new’ investment in greenfield projects or in expansion and modernisation gross flows are more appropriate, even if there are some firms that were borrowing to make investments in other financial assets to beef up profits.

Chart 1 provides figures on the different kinds of gross flows to the private non-financial corporate sector from the rest of the economy and the rest of the world. The category ‘other’ refers to trade credits and other advances and is not significant from the point of view of financing investment. Keeping that in mind, the chart shows equity finance was significant in all years, and equalled or exceed the combined contribution of debt securities and borrowing in all years excepting 2012-13. Moreover, corporate deposits, using which firms can avoid bank intermediation to mobilise resources from households and other sources was also not significant.

This picture negates the view that India is largely a bank-based system, with borrowing accounting for a dominant share of corporate finance. This dependence on bank borrowing should have increased after liberalisation, since the process substantially reduced the role of the development finance institutions in financing corporate activity and encouraged the transformation of two of them (ICICI and IDBI) into commercial banks.

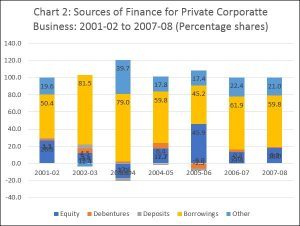

The view that the Indian financing system is bank based is supported by two other pieces of evidence. First, if we consider the post-liberalisation high growth years, from 2002-03 to 2007-08, when the ratios of investment to GDP and private investment to total investment in the economy peaked, flow-of-funds data (Chart 2) point to the overwhelming dominance of borrowing in the increase in total financial liabilities of “Private Corporate Business”. Secondly, this borrowing-financed investment spree that led to a significant increase in project failures is seen as underlying the large, corporate-loan-dominated, non-performing asset portfolio of the commercial banks.

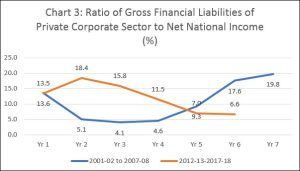

The RBI explains this transformation of the financing pattern of the corporate sector as follows: “The financial resource gap of the PvNFCs (private non-financial corporations) declined steadily from 2012-13 to 2017-18 from a deficit of 5.3 per cent of NNI (net national income) to 1.5 per cent. Lower investment demand, increased savings and lower inflation has benefited PvNFCs.” The smaller resource gap can be taken as evidence of a greater use of internal resources, and the pattern of financing of a shift from debt to equity. This view, however, is only partially correct. It is true that one important factor explaining the fall in the share of borrowing in total financing is “lower investment demand” or put more clearly falling investment and less projects to finance. If we examine the ratio of gross financial liabilities to net national income in the two periods being discussed (2001-02 to 2007-08 and 2011-12.13 to 2017-18), we find that it rose from 4.1 per cent in 2003-04 to 19.8 per cent in 2007-08, whereas it fell from 18.4 per cent in 2013-14 to 6.6 per cent in 2017-18 (Chart 3). The ratio of gross capital formation to GDP on the other hand rose from 24.6 to 39.0 per cent in the first period and fell from 39.0 to 33.7 per cent, before rising in the last year to 35.5 per cent, in the second period. This indicates that the financing requirement relative to national income of the private corporate sector rose sharply when the investment ratio rose and fell when the investment ratio declined or remained subdued.

Moreover, to the extent that investment occurred in the recent period, banks were clearly not eager to finance them. First, because they were burdened with large, corporate, non-performing assets, and did not want to further increase their relative exposure to the corporate sector. Second, being burdened with non-performing assets they possibly did not want to finance projects that were potentially non-performing given the business environment that had already led to depressed investment. In the circumstances, whatever investment occurred was substantially financed with internal resources (which kept the financing requirement from the rest of the sectors low), and that financing requirement was largely met with equity.

Thus, the flow-of-funds data that points to a degree of disintermediation, with private non-financial corporations reducing their dependence on banks and other financial institutions, is not a sign of change in financing pattern, but evidence of a slowdown in investment and a greater wariness on the part of financial institutions on increasing their exposure to the corporate sector in this depressed environment. However, the data on GDP have till recently not revealed this state of affairs, with the now controversial figures pointing to the continuation of relatively high growth.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on July 15, 2019)